Investigating AI datasets - OpenImages

(Disclaimer: This post is also featured on the Data Culture blog)

Today’s statistical algorithms, including a majority of machine learning and AI techniques, rely on large amounts of training data. Understanding what is in these datasets, how they are collected, and how different groups are represented is important, as biased data often leads to biased algorithms. Inspired by the recent work of Emily Bender et al. and Kate Crawford’s new book Atlas of AI I decided to look at one popular dataset - the Open Images Dataset. Open Images is a dataset similar to ImageNet, it contains approx. 9 million images, annotated with image-level labels, bounding boxes, segmentation masks, etc.

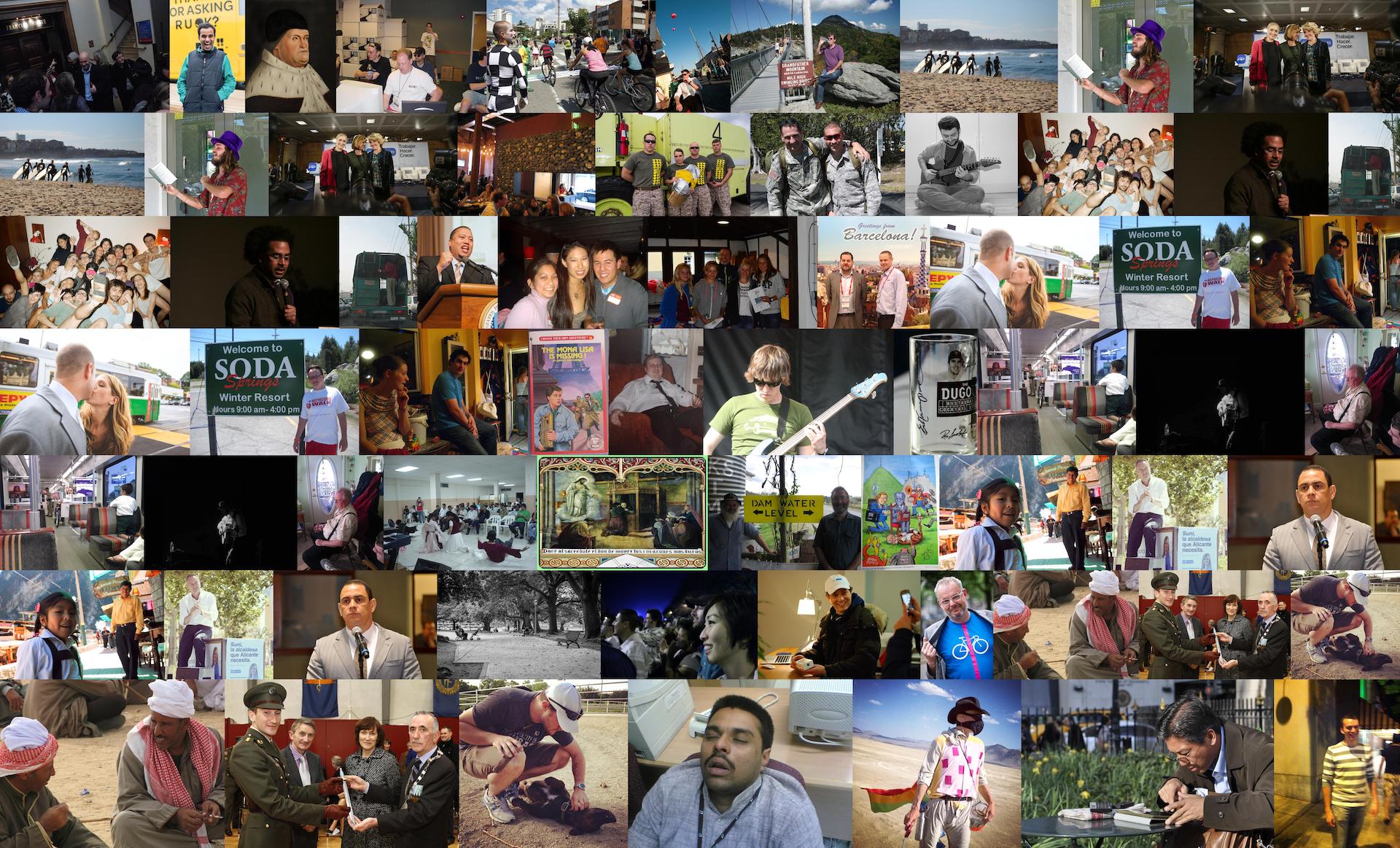

Research has already shown that Open Images has issues when it comes to where images are from, with more than 50% of images coming from just 4 countries (US, UK, France and Spain). However, here I want to dig a bit deeper into the dataset itself. I’m not interested in where images are from, rather I want to know what they actually depict. For instance, the image above is a random sample of the banana class. There are images of single bananas, stalks of bananas, banana bread, somebody using a banana as a phone, and even drawings/art of bananas. In total there are 743 images of bananas in the dataset.

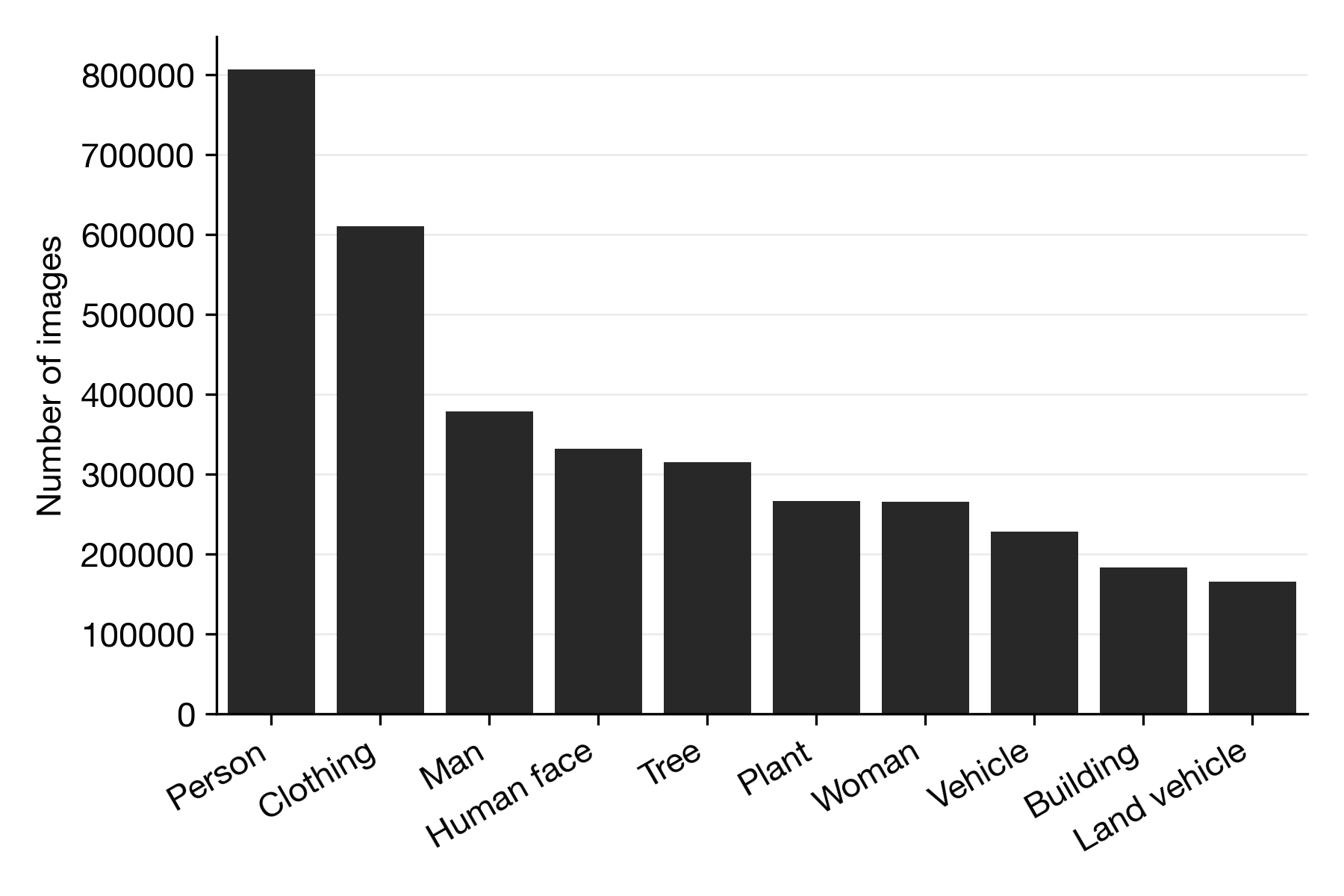

Banana is just one type of label in the 601-label large dataset. If we look at the 10 most popular labels (see figure above) we see that around 800.000 images have the label “Person” (~ 9% of all images), followed by clothing with 600.000 images (~ 6.6% of images). We also see there are also more images labeled “Man” than “Woman”. Further, here, we also notice a peculiarity, for instance, there is a label called “Human face”. I’m not sure why “Human” is added, because there are no other types of faces in the dataset. Anyway, that got me thinking, what other “Human”-like attributes are in the dataset?

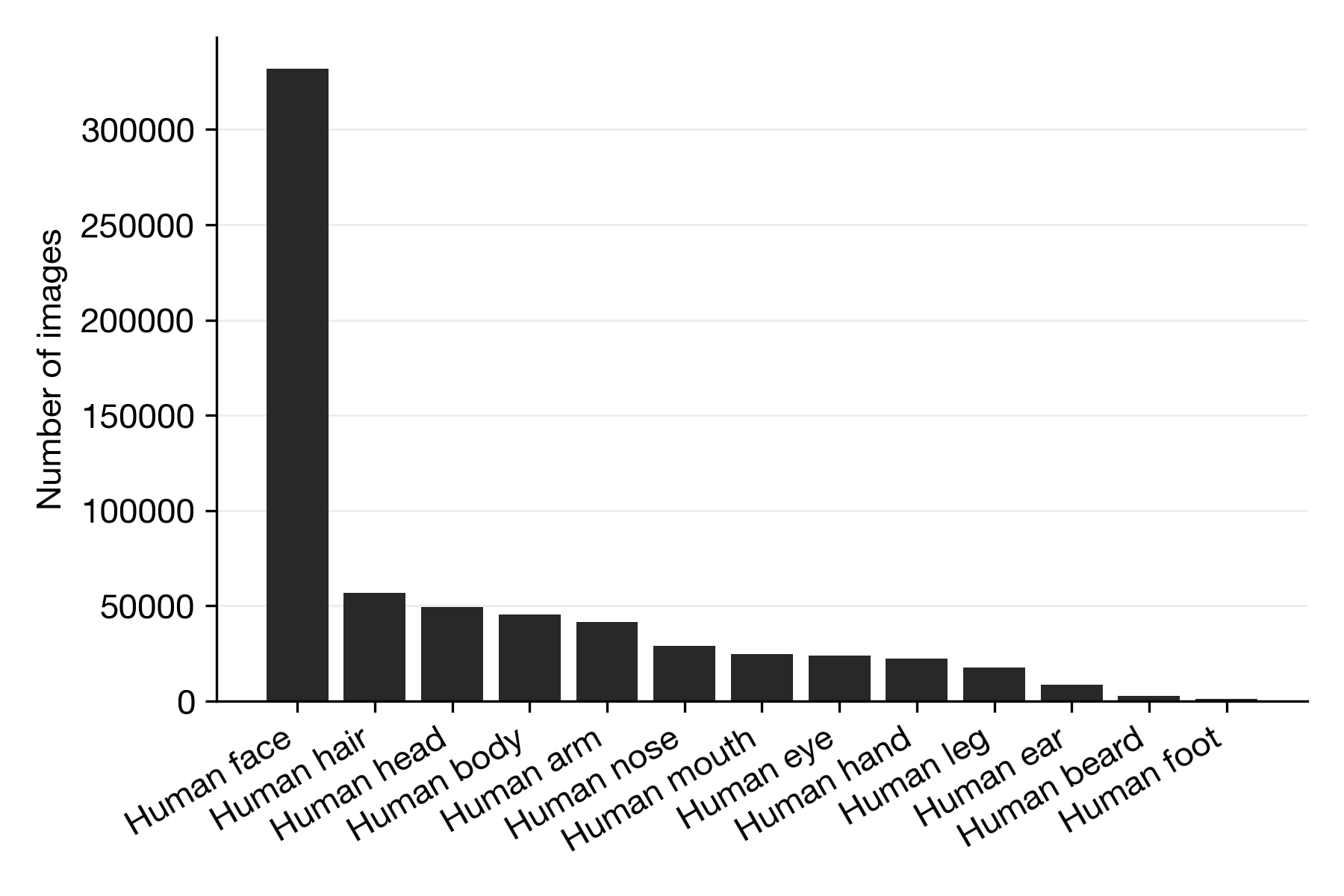

In the figure above we see there are 13 different “Human x” type labels, from human face, to hair, body, nose, eye, beard, to foot. By far, the most popular, and larger than all the other combined, is “Human face”. The least popular is human foot, with only ~ 1000 images (but still more popular than the “Banana” label). The focus on human faces rather than any other body part tells us something about which purpose this dataset was assembled for, and most likely it looks like its for facial recognition purposes. Please note that developments in facial recognition algorithms have been heavily funded by various defense and intelligence agencies - and have been found to be heavily biased in terms of gender and race - see Atlas of AI for more info.

If we dig further into the “Human x” categories and plot a random subset of the images labeled with “Human beard” we see that it mainly represents one specific demographic - predominantly the beard of white men.

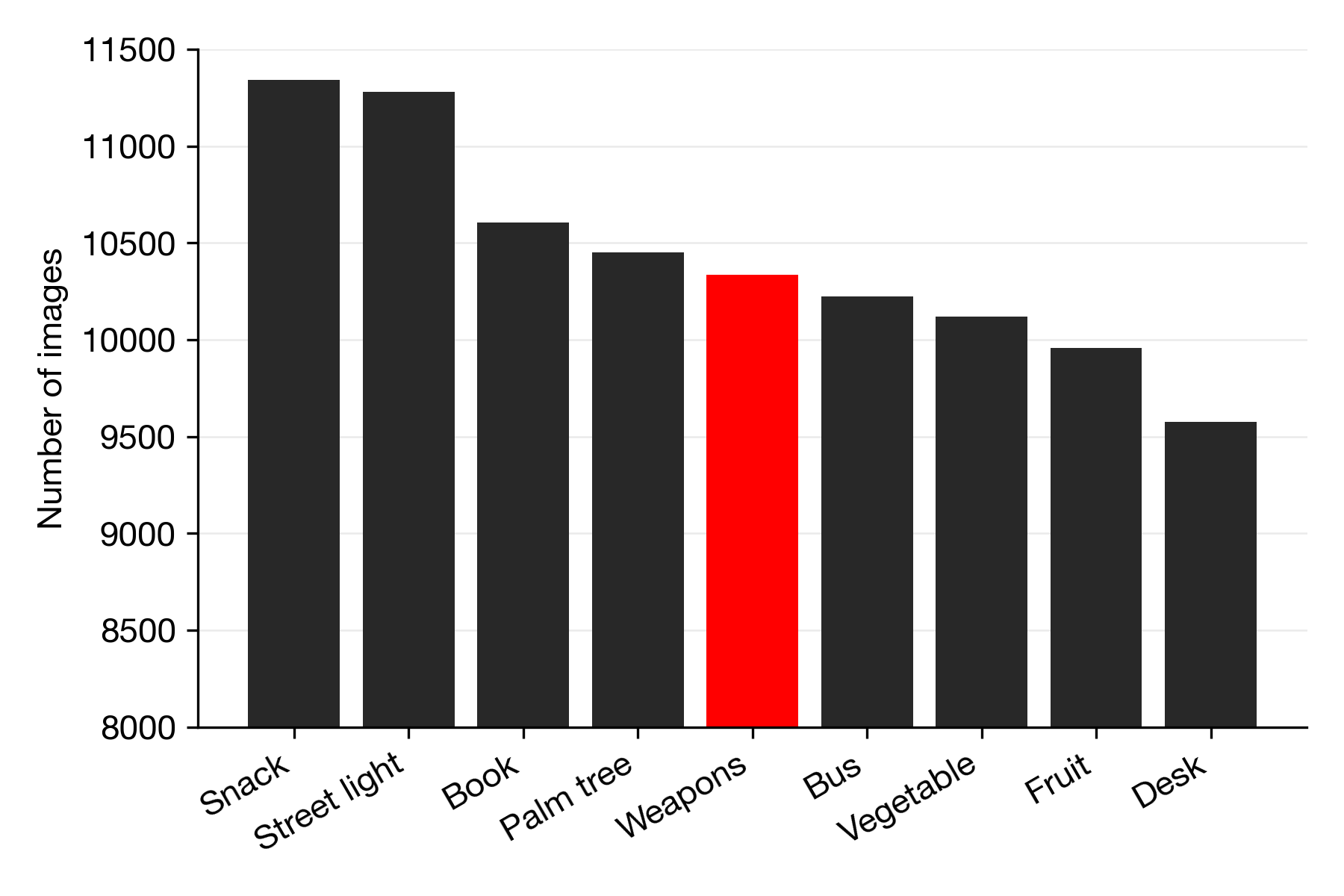

But that is not all. If we keep digging we eventually find other issues. For instance, the Swimwear label mainly has images of skimpily dressed young women (as perceived through a male gaze). The label Brassiere has the same issue. However, the thing that surprised me the most is the existence of labels relating to weapons. This includes labels like: Weapon, Rifle, Tank, Handgun, and many others. Which raises the question: why are they even in this dataset? It is difficult to say why the developers of OpenImages chose to include these in the dataset. My guess is that the heavy involvement of DARPA, IARPA, and many other defense and military agencies in AI, and the money they have thrown into the development of AI tool for their purposes (e.g. facial recognition, etc.), has biased the sample towards weapons.

Now, you might think, how big is this problem? There cannot be that many images? If we look at the amount of images labeled with a weapon-category (Weapon, Rifle, Tank, Handgun, Missile, Shotgun, Sword, Bow and arrow, Submarine, Bomb) we find there 10.000 of them, a substantial number. This is comparable to the number of images labeled as Book, Bus, Vegetable, and Fruit (see below figure).

It is an open question why our image recognition AI tools should be equally good at identifying books and fruit as weapons. To summarize, do not assume that because a dataset is big, or has been used by many people / many academic papers, it is of good quality. Often datasets are constructed from easily scraped datasources. As such, many widely used big datasets contain significant biases and limitations. To read more please check out Kate Crawford’s book.